Augusta Savage, the first African American to open her own art gallery

When Augusta Savage arrived in New York at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, she only had a few dollars in her pocket. However, she quickly found herself in the company of the prominent writers and activists of the 1920s, including W.E.B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey. Savage joined them while simultaneously combating poverty and racism. A plaster edition of Savage’s well-known Gamin was offered in the Two-Day Fine Art, Antique, Jewelry Auction, presented by Case Antiques.

Her work, though often overlooked, captured a distinct era of American history. As the first African American woman to open her own art gallery, Savage divided her time between creating art and supporting the next generation

Savage was born to a devout Methodist minister who “almost whipped all the art out of [her].” Despite this difficult start, Savage was relentless in her pursuit of education. In 1923, she applied to a summer art program in France. Though accepted into the program and corresponding scholarship, the French government refused her after learning she was Black. “As soon as one of us gets his head above the crowd there are millions of feet ready to crush it back again…”. Savage wrote in her public response, which was printed in the New York World. “For how am I to compete with other American artists if I am not to be given the same opportunity?”

It took six years of activism, but Savage was eventually permitted to study in France. That struggle permanently fused her ideals with Augusta Savage art, which explores the African American experience in the Jim Crow era. During the Great Depression, Savage found work by running an art school and creating portrait busts of her fellow African American activists. However, Roberta Smith, writing for The New York Times, identifies the artist’s portraits of everyday people as her strongest works: “Savage’s radicalness lies in her determination — one shared with many Black artists today — to populate art with active representatives of Black life.”

She created her most famous portrait of a young African American boy, titled Gamin, with that goal in mind. Modeled after her nephew, the bust was intended to represent the countless young boys who populated the streets of her city. Savage could not afford bronze when she made the piece, instead using white plaster, brown paint, and shoe polish. “What’s so remarkable about this work is that, quite simply, it presented an African American child in a realistic and humane fashion,” says Wendy N.E. Ikemoto, the coordinator of a recent exhibition of Savage’s work at the New-York Historical Society.

A plaster and bronze patina version of Gamin will soon come to auction with Case Antiques. The title of the work is carved on the boy’s chest, and it is signed by the artist on the back. Bids will begin at USD 3,400 against a presale estimate of $7,000 to $8,000. In several past events, the Augusta Savage sculptures reached well above those figures. John Moran Auctioneers sold an edition of the piece for $35,000 in 2007, and it was more recently auctioned for $68,750, more than twice the high estimate.

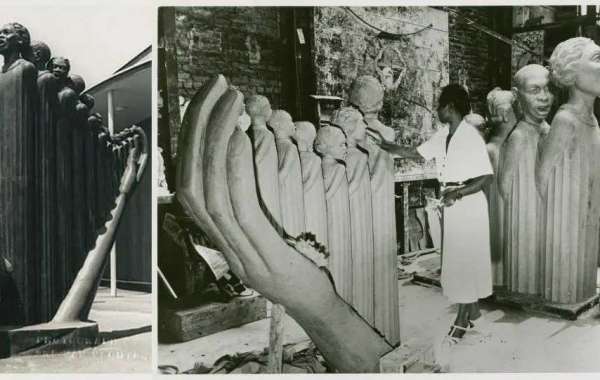

Few of Savage’s works have survived, due in part to her lack of access to enduring materials. The Harp (Lift Every Voice and Sing), a large sculpture created for the 1939 New York World’s Fair in Queens, was the artist’s greatest work and greatest loss. She spent two years on the piece, which shows 12 Black children ordered to resemble the strings of a harp. Despite receiving acclaim at the Fair (“Miss Savage’s creation… is commented upon by practically everyone who passes,” wrote a Baltimore newspaper), Savage lacked the funds to store the sculpture or cast it in bronze. It was consequently bulldozed. When surviving miniatures of The Harp reach the market, they draw attention: one sold for $9,500 at Swann Auction Galleries in 2006 while another reached $23,750 in 2014.

Savage recognized the temporary nature of her work. She preferred to view her legacy as the skills she taught her students and followers in Harlem, many of whom would later establish successful careers. “She’s been lost to history, compared to her well-known students, who had increased attention,” says Ikemoto. “… She’s a great reminder of the crucial role of having a multiplicity of voices in the public space.”

Media source: AuctionDaily.